In March 2014, a money laundering network was discovered in a car wash in Brasilia. It was the tip of a giant iceberg of corruption.

The epicenter of the political earthquake that punishes Latin America for years was initially located at a service station in Brasilia, a few kilometers from the Presidential Palace of Planalto and the seat of Congress in Brazil.

In that service station that included a car wash (“Lava Jato”, in Portuguese), the investigators of the Brazilian Federal Police discovered a money laundering network that seemed to involve different politicians. But the true dimension of the operation, which just turned five years old (started on March 17, 2014), was coming to light in a few droppers in the following months.

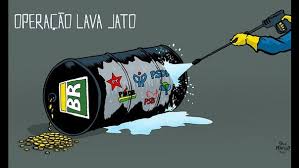

The case “Lava Jato” is considered today as the largest anti-corruption operation in the history of Brazil and has profoundly changed the South American giant, until a few years ago one of the global emerging powers.

The operation, which began investigating a corrupt plot in Brazil’s state oil company Petrobras, also spills over several countries in the region, where it has already produced strong political scuffles in countries like Colombia and, above all, Peru, where several former presidents are accused.

In Brazil, the scandal continues to shake the foundations of the political and economic elites of a country in permanent crisis. The “Lava Jato” made “a portrait of a corruption that has deep roots in our history”, explained in 2017 Deltan Dallagnol, one of the prosecutors in charge.

Among those involved are powerful businessmen such as the former CEO of the construction company Odebrecht, Marcelo Odebrecht, or former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, the most famous defendant, imprisoned in Curitiba for almost a year.

Since the operation was initiated 5 years ago and 4 days ago, the Justice has already handed down a sentence in 50 trials and given 242 convictions against 155 people. The sum of the sentences totals 2,242 years and 5 days.

Lula, an icon of the left for the success of his two terms between 2003 and 2010, was sentenced in second instance, in April last year, to more than 12 years in prison for having received a luxurious apartment in the seaside resort of Guarujá. , in San Pablo, as a bribe for having favored a construction company in public works, according to the judges.

In addition to former conservative president Michel Temer, arrested Thursday in Sao Paulo, dozens of deputies, former governors and officials are also investigated.

Two other Brazilian ex-presidents, Fernando Collor (1990-1992) and Dilma Rousseff (2011-2016), both dismissed by Congress, are being prosecuted in proceedings equally linked to Lava Jato, while a third party, José Sarney (1985-1990) ), was accused of receiving bribes for facilitating contracts rigged with a subsidiary of Petrobras, but so far he does not respond to any trial.

According to the investigations, the corrupt scheme worked mainly around Petrobras, located at the center of the Brazilian economic boom of the past decade due to high oil prices. Numerous private companies systematically bribed officials and politicians to secure contracts with the state giant.

That modus operandi, the researchers later discovered, extended to other sectors such as construction or food, where the Brazilian business expanded its business in large part thanks to the collusion with the political class.